If you are a PhD candidate or postdoc, you probably spend a large part of your day surrounded by text. Articles, manuscripts, reviewer reports, emails, student work – in one sense, your whole job is reading and writing. And yet, a lot of researchers quietly carry the same uncomfortable thought: other people seem to read more, know more, and somehow stay ahead of the conversation in their field.

This article is about that quiet gap and what you can realistically do about it. Instead of asking you to work longer hours, I want to look at reading as a deliberate practice that supports your academic productivity over years, not just weeks. The basic idea is simple: when you treat reading as serious work and give it a reliable place in your day, it turns into a silent but powerful advantage for your thinking, writing, and career decisions.

What Buffett and James Clear understand about (academic) work

There is a well-known story about Warren Buffett visiting students and being asked how to prepare for an investing career. The students were probably expecting something about complex models or special analytic tools. Instead, Buffett refers to a stack of reports and basically says: read. He describes how he used to read about 500 pages per day and compares knowledge to compound interest. You slowly build up an understanding that becomes harder and harder to match if others are not doing the same.

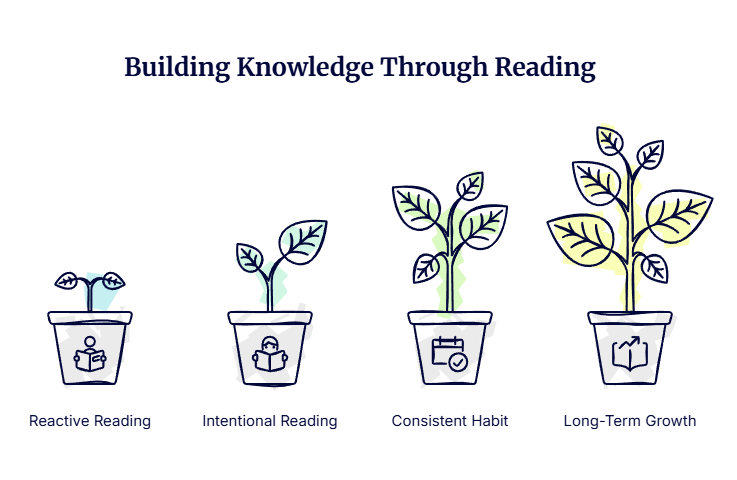

James Clear took this idea and turned it into a specific habit. When he examined his own life, he realised that although he was reading all the time, most of it happened by accident. If something interesting appeared on his screen, he clicked. In other words, his reading was reactive. The internet decided what he saw next. Books, which usually contain more carefully edited and better researched content, were constantly pushed aside by shorter, more immediate pieces.

To change that, he designed one simple rule: read 20 pages at the start of the day. After waking up, he would drink a glass of water, note three things he was grateful for, and then open a book. Twenty pages, every morning. Over several weeks, he noticed that this small ritual carried him from one book to the next, and if you project that pace forward, it adds up to roughly thirty to forty books per year. Not because he spent whole weekends lost in reading, but because he created a tiny, reliable structure that protected this activity from the rest of the day.

The quiet routine behind expertise

Warren Buffett has said that knowledge builds like compound interest and reportedly spent about 80% of his working hours reading or thinking, at times aiming for 500 pages per day.

For academia, the specific numbers are less important than the principle. There is work that is visible – papers, grants, talks – and work that shapes your capacity to do those things well. Deep, continuous reading belongs to this second category.

Reading as a driver of academic productivity

When people in universities talk about academic productivity, they usually point to outputs: how many papers you have published, how many projects you are involved in, which conferences you attend, how your teaching evaluations look. All of that matters. But underneath these visible results sits something slower and harder to measure: the quality of your understanding.

Regular, structured reading quietly strengthens that foundation. When you read beyond what you strictly “need” for the next deadline, you start to see your field differently. You notice how certain arguments repeat under different labels. You recognise when a “new” paper is really a slight variation on a familiar pattern. You remember where particular methods came from and what their limitations are.

This has very concrete effects on your academic productivity. Writing becomes less painful because you have sentences, arguments, and structures in your head from the texts you have absorbed. You make decisions faster: which paper to cite, how to position your contribution, which journal to aim for. You feel more grounded when you review someone else’s work or stand in front of a class. Instead of constantly feeling like you are catching up, you slowly shift into a position where you can see the bigger picture.

The difficulty is that reading almost never feels urgent. There is always another email, another dataset, another administrative task that looks more pressing. That is why a small, protected habit – like those twenty pages in the morning – can make such a difference.

From reactive to intentional reading

Think about how you usually read during a normal working day. Many researchers start by opening their email and following a link, then checking social media and seeing a discussion about the latest preprint, then clicking on a news article recommended by the algorithm. None of this is wrong, but it means your reading is driven by whoever happens to reach you in that moment.

Intentional reading works the other way around. You decide in advance what is genuinely important for your research, your teaching, or your broader development as a scholar. Then you create a small container in your day that is reserved for that type of text. This could be a classic book in your field that you have always postponed, a careful methods monograph that will sharpen your next study, or a set of foundational articles that give you a more stable sense of the field’s history.

When this container sits at the beginning of your day, before the world starts demanding your attention, the change can be surprisingly significant. You are not trying to force a big reading block into an already overloaded afternoon. You simply start your day by investing half an hour in your own intellectual growth, and only then move into the rest of your tasks.

Why 20 pages matter

By reading just 20 pages each morning, James Clear moved through about seven books in ten weeks, which projects to roughly 36 books per year, even if nothing else in his day changes.

The beauty of this approach is that it is modest. Twenty pages are rarely intimidating. On a difficult morning, you might read a little less; on a calmer day, you can go beyond that number. But the anchor remains: there is a moment each day where reading has first claim on your attention.

Turning reading into visible progress

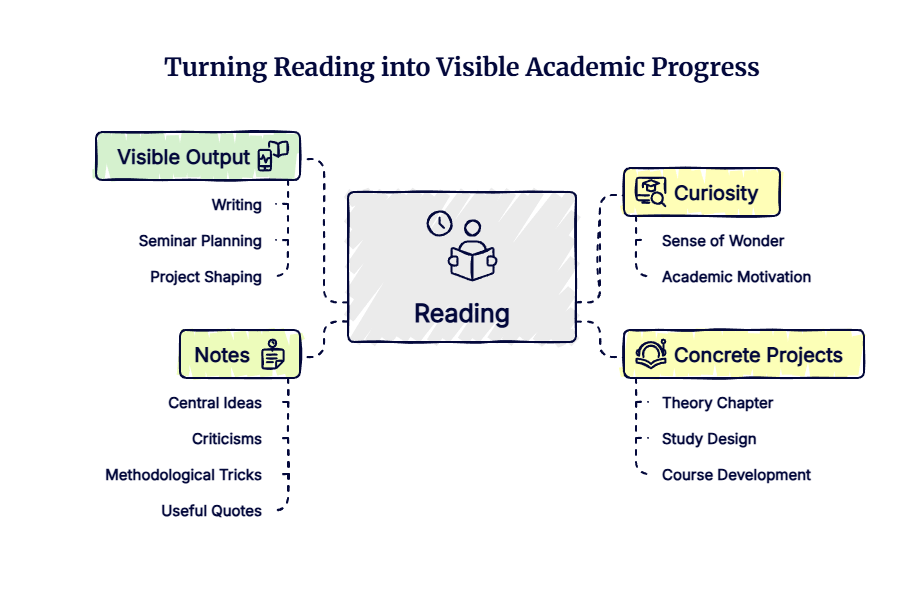

Of course, reading purely for its own sake can already be valuable. It can restore a sense of curiosity and remind you why you entered academia in the first place. At the same time, if you want your reading habit to support your academic productivity in a more direct way, it helps to connect it to your concrete projects.

One simple way is to keep a very short list of books and key articles that matter most for your current work. You might decide that, for the next months, your morning reading will focus on a small cluster of texts for your theory chapter, your next study design, or a new course you want to develop. After each session, you jot down a few sentences: a central idea, an important criticism, a methodological trick, a quote that might be useful later. These notes do not have to be polished. They exist to prevent your reading from dissipating into vague impressions.

Over time, this creates a bridge between your quiet reading practice and your visible academic output. When you sit down to write, you already have fragments waiting for you: summaries, reflections, and questions that grew naturally out of your daily sessions. When you plan a seminar, you can return to the notes from your morning reading and turn them into teaching material. When you shape a new project, you will have a richer map of existing work in your mind.

Reading as a long-term strategy

If you want to stay in academia, you are not just building a CV; you are building a life. That life will feel very different depending on whether you constantly experience yourself as a slightly underprepared worker, or as someone who is steadily deepening their understanding of their field.

Treating reading as a non-negotiable part of your workday is one way to move towards the second version. You do not have to match Warren Buffett’s marathon sessions. You do not need exotic productivity systems. A glass of water, twenty pages, and a protected half hour before the rest of the world comes in are already enough to create movement.

This does not look dramatic from the outside, and that is exactly the point. The most important shifts in academic productivity are often quiet: a little more clarity in your thinking, a little more courage in your writing, a little more confidence in how you navigate your field. Reading, done consistently, supports all of these.

Start small, stay kind to yourself, and remember that this is not about winning a reading contest. It is about building the kind of intellectual life that will sustain you over the many years a research career can span.