When researchers ask me how to design their ideal day for academic writing, they often expect a recipe:

- Find your peak performance time.

- Block two or three hours of uninterrupted writing.

- Turn off email, close the door, done.

This can help—but only up to a point.

The real problem usually sits one step earlier:

when your calendar says “writing”, you probably don’t actually know what that means for the specific project in front of you.

And if you are unclear, your brain will respond with the familiar mix of resistance, procrastination, and low-grade guilt.

So before you optimise your routine, let’s do something much more fundamental:

clarify what “academic writing” actually includes in your work, and who you need to be for each part of it.

Why Generic Writing Advice Often Fails in Academia

Most productivity advice treats writing as one uniform activity:

sit down, focus, type words.

But academic work doesn’t work like that. On any given day, you might be:

- cleaning data

- coding interviews

- thinking through a theoretical argument

- drafting a messy introduction

- tightening the discussion section

- responding to co-author comments

- formatting references

Are all of these “writing”? In the broad sense: yes.

And that’s exactly the problem.

When you use one word—“writing”—for activities that are cognitively and emotionally completely different, your planning becomes fuzzy:

- You block “writing time” in the morning but spend it fixing a minor formatting issue.

- You intend to “write”, but what you actually need is unhurried thinking about your argument.

- You feel unproductive after a day of data analysis, because it didn’t feel like “real writing”.

The result: your schedule looks full, but your progress feels thin.

To change that, we need a more precise vocabulary for what you actually do.

What “Writing” Really Includes in Academic Life

Let’s broaden the lens and name the different activities that often get thrown into the writing bucket.

For a typical paper, “writing” can include:

1. Exploratory thinking and idea generation

You’re sketching on paper, talking with colleagues, reading loosely, connecting dots.

This phase is fuzzy, non-linear, sometimes a bit chaotic.

2. Drafting (the Hemingway “write drunk” phase)

You put rough text on the page: first versions of introduction, methods, or discussion.

The goal is movement, not perfection. Sentences may be bad; that’s fine.

3. Analysis and interpretation

You run statistical models, code qualitative data, or do close readings.

This is where you ask: “What is actually going on in this material?”

4. Structuring and argument-building

You decide how the story of your paper will unfold: which result goes where, how you connect theory and findings, what to foreground and what to cut.

5. Editing, polishing, and formatting (the “edit sober” phase)

You improve clarity, tighten paragraphs, fix references, adjust tables, harmonise terminology.

This requires a more precise, careful mindset.

6. Relational writing work

You might not have text open at all but you are:

- discussing an idea over coffee

- negotiating contributions with co-authors

- revising based on reviewer feedback

None of these look like “classic writing”, but they deeply shape the text that will eventually exist.

All of this is academic writing in a broad sense.

But each of these sub-activities asks for something different from you.

Different Activities, Different Versions of You

If you try to do all of these with one generic “writing mindset”, you will feel constant friction.

A more helpful way of thinking is:

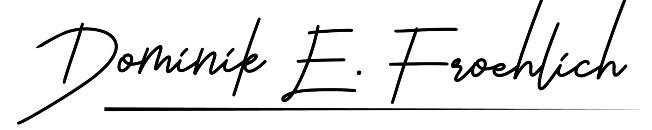

Which version of myself is needed for this specific activity?

Here’s one way to slice it:

The Explorer

Best for: exploratory thinking, reading loosely, early-stage idea generation.

What you need: curiosity, openness, tolerance for not knowing.

Context that helps: a notebook, low pressure, maybe a café or a walk, minimal expectations of “output”.

The Drafter

Best for: messy first drafts of sections.

What you need: willingness to produce imperfect text, medium focus, some momentum.

Context that helps: a time-limited block (e.g. 25–50 minutes), document open, clear small target (“one ugly paragraph about X”).

The Analyst

Best for: data analysis, coding, model-building, careful interpretation.

What you need: sustained focus, analytical clarity, low distraction.

Context that helps: quiet environment, access to all needed materials, a rested brain (often better earlier in the day).

The Architect

Best for: structuring the paper, deciding flow, rearranging sections.

What you need: overview, decision-making, the ability to zoom out.

Context that helps: big monitor or printed draft, time to think without interruption.

The Editor

Best for: polishing text, fixing references, formatting.

What you need: attention to detail, but not necessarily peak creativity.

Context that helps: smaller time slots, later in the day, when you’re a bit tired but still functional.

The Networker

Best for: co-author meetings, feedback conversations, idea coffees.

What you need: communicative energy, openness to negotiation.

Context that helps: scheduled meetings, some notes prepared, clear purpose for the conversation.

When you name these “selves” or modes, something important happens:

your calendar can become specific.

Instead of “writing 9–11”, it can say:

“Architect work on paper X: decide structure of results section”.

And that is a much more realistic appointment.

A Practical Exercise: Map the Writing Work of One Project

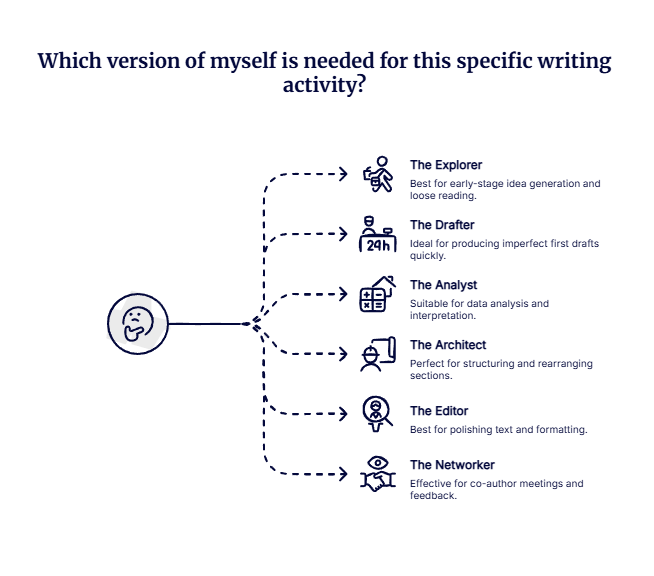

Let’s make this concrete. Take one current writing project—a paper, your thesis chapter, a grant proposal—and walk through this simple exercise.

Step 1: List all the sub-activities

Grab a blank page and write down every task that is part of “writing this thing”.

For example:

- clarify research question

- run additional model for robustness check

- write first draft of methods

- rewrite introduction paragraph 1–2

- integrate comments from co-author on results section

- prepare response-to-reviewers document

- check references and formatting

Try to be specific. “Work on introduction” is too vague.

“Draft 200 words on why this topic matters for X field” is better.

Step 2: Assign each task to a “version of you”

Next to each task, note which mode it belongs to:

- Explorer, Drafter, Analyst, Architect, Editor, Networker (or your own labels).

You might notice patterns:

- Most of your current tasks are analytical and architectural.

- Or: you haven’t actually done much exploratory thinking yet.

- Or: everything seems stuck because you’re trying to edit text that doesn’t exist.

Step 3: Match activities to energy and context

Now ask three simple questions for each mode:

-

When in the day do I usually have the right energy for this?

(Morning, mid-day, late afternoon?) -

What context do I need?

(Silence, library, office, café, online meeting?) -

How much uninterrupted time does this realistically require?

(15 minutes, 45 minutes, 2 hours?)

You might find, for example:

- Analyst and Architect work fit best in your protected morning hours.

- Drafter tasks can work mid-morning or early afternoon.

- Editor tasks are perfect for late afternoon when you’re more tired.

- Networker tasks simply need clear scheduling with others.

This is the level of clarity you need before asking, “What should my ideal writing day look like?”

From Clarity to Calendar: Your Next Step

Once you’ve done this mapping exercise for one project, designing a writing routine becomes much more straightforward:

- You are no longer scheduling an abstract “writing block”.

- You are scheduling a specific mode plus a specific task.

A calendar entry like “Writing” invites procrastination.

A calendar entry like “Drafter mode: messy first pass on methods, 45 minutes” invites action.

And this is the main point:

The quality of your writing routine depends less on the perfect time of day and more on how precisely you define what “writing” is for this project right now.

So before you optimise for peak performance, take one step back:

- Define your sub-activities.

- Name the versions of you they require.

- Match them to realistic times and contexts.

Only then does the question “How do I design my ideal academic writing day?” become answerable in a meaningful way.