Even the best plan fails if basic conditions aren’t secured.

“Pete” had done everything right: PhD finished, targeted postdoc applications sent, clear narrative, aligned labs. Yet no offer came—and frustration set in.

In coaching, this is common. You can tweak positioning, timing, and your CV story—but sometimes a single constraint changes everything. For Pete, it was a visa about to expire. Suddenly, all strategy depended on one simple fact: legal permission to stay in the country.

This is a trap many researchers fall into. We focus on ideal goals—labs, projects, five-year plans—while forgetting the practical constraints that make any plan possible: visas, funding, health, income, family obligations. Not exciting—but decisive.

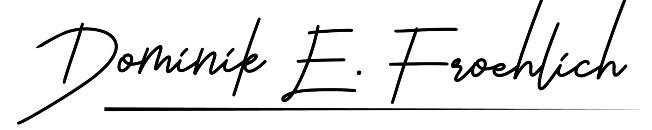

Why Academic Career Planning Often Breaks at the Foundation

In academic careers, it’s easy to confuse strategy with feasibility.

Strategy is what you do when the playing field is stable enough to move pieces around: Which labs to apply to, how to position your profile, how to communicate fit, how to create options?

Feasibility is the question underneath: Do you have the conditions that allow any of those moves at all?

Feasibility can be mundane:

If feasibility is shaky, strategy becomes fragile. Not because the strategy is bad — but because the runway is too short.

And when runway is short, people make career decisions under pressure. They accept mismatched roles. They stay too long in unsustainable conditions. Or they burn out while trying to “push through” a constraint that cannot be negotiated away.

The Priority Mistake: Optimizing “Ideal” Before Securing “Possible”

Many researchers are trained to think in ideals:

That seems useful until it blocks the deeper question:

What must be in place for any of this to work at all?

For Pete, visa timing wasn’t a detail. It was the foundation. Without it, the rest of the plan is hypothetical.

This isn’t pessimism—it’s good planning. Once you surface true constraints, you can set priorities that actually protect your options.

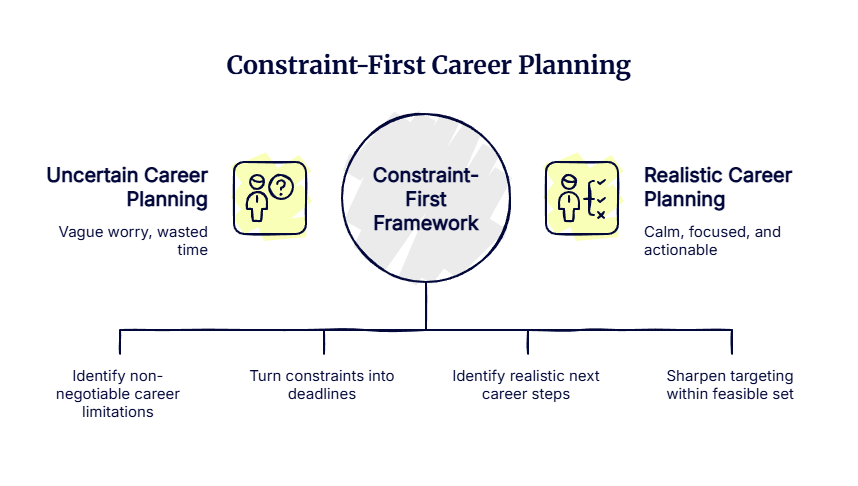

A Simple Constraint-First Framework for Setting Priorities

Here’s a practical way to approach career planning when uncertainty is real.

1) List constraints before goals

Write down non-negotiable constraints, not preferences.

Examples:

- Visa deadlines / legal status

- Funding end dates, bridge funding needs

- Minimum monthly income, savings runway, debt obligations

- Health boundaries, caregiving duties, mental load

- Location restrictions, partner employment constraints

Be blunt. The point is not to judge the constraints. The point is to see them.

2) Translate constraints into deadlines and thresholds

Constraints matter because they create time pressure and minimum requirements.

Turn each constraint into either:

- a deadline (e.g., “visa decision needed by March 15”)

- a threshold (e.g., “minimum monthly income of X,” “must avoid uninsured gap,” “needs 8 hours/week for caregiving”)

This is where vague worry becomes concrete planning.

3) Define the “feasible set” of next steps

Ask: given these deadlines and thresholds, what options are realistically executable in the next 3–6 months?

This is not lowering ambition. It’s narrowing the search to options that actually work.

For Pete, the feasible set included:

- Postdoc positions that can sponsor the right visa category

- Short-term research affiliate roles to maintain legal status

- Geographic flexibility if sponsorship is limited

- Parallel paths outside academia to stabilize legal status

Constraints define the feasible set. Strategy comes after feasibility.

4) Only then optimize strategy inside the feasible set

Once feasibility is secured, strategy becomes powerful again:

- Sharper targeting

- Cleaner positioning

- Stronger networking outreach

- Better application cadence

- Clearer narrative alignment

This is where priorities become calm, not frantic—because they rest on reality, not hope.

What This Changes Emotionally (and Why It Matters)

Constraint-first planning reduces hidden uncertainty.

Many researchers carry quiet anxiety, often interpreted as personal inadequacy:

Sometimes, the real issue is structural: conditions are unstable.

Acknowledging constraints lets you stop moralizing them.

Once treated as real inputs, you can make ambitious and sustainable decisions.

A Small Action You Can Take This Week

Write two columns:

- Ideal next step – what you’d choose if everything were easy

- Required conditions – what must be true for it to be executable

Pick one required condition you can influence in the next 72 hours:

This is what setting priorities looks like when your goal is progress you can sustain.

Closing Thought

In academic careers, decisive moves are rarely glamorous. They’re administrative, legal, financial, practical.

Take them seriously, and your next steps stop being fragile ideals—they become viable paths.

Ask what would be ideal—but never skip the deeper question:

What must be in place for any of this to work at all?